Trigger Warning: this article discusses white supremacy, police brutality, and features an image of Ahmaud Arbery’s final moments.

The day after my family relocated to Texas from London, where we lived for seven years, police officer Darren Wilson fatally shot 18-year-old Mike Brown in Ferguson, Mo. Brown’s murder sparked weeks of protests and gave new, worldwide attention to the rapidly growing Black Lives Matter movement.

My life in London didn’t prepare me to grapple with these events or the awful litany of similar slayings preceding and succeeding Brown’s. In England, the police don’t even carry guns. The American public’s vehement defense of Wilson for exercising his rights as an officer astounded me.

By the time Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on George Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes, slowly collapsing his windpipe, seven years had passed since Brown’s murder. Some things had changed — primarily my understanding of race in America — but systemic racism had not.

This time the international outcry felt undeniably greater than in 2014. One crucial difference is the video documentation of Floyd’s death. The video was posted across every social media platform: various posts of it collected over 1.4 billion views in the week after his murder according to an L.A.-based analytics firm, Pex.

If we’ve learned anything from systemic police killings of Black people, it’s that images of atrocity and horror are necessary for facilitating social change. They play an essential role in influencing public opinion and legislation, like the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act introduced in 2021. However, the public execution of Black people has become a voyeuristic cultural spectacle for Americans. We do not need any more videos of Black people dying at the hands of armed officers to know police brutality is an abhorrent problem.

I do believe there’s some merit in posting videos like George Floyd’s, especially to uplift the movement to fundamentally change the role of police departments across the country. Nevertheless, that merit must be measured against the trauma videos of immense suffering inflicts.

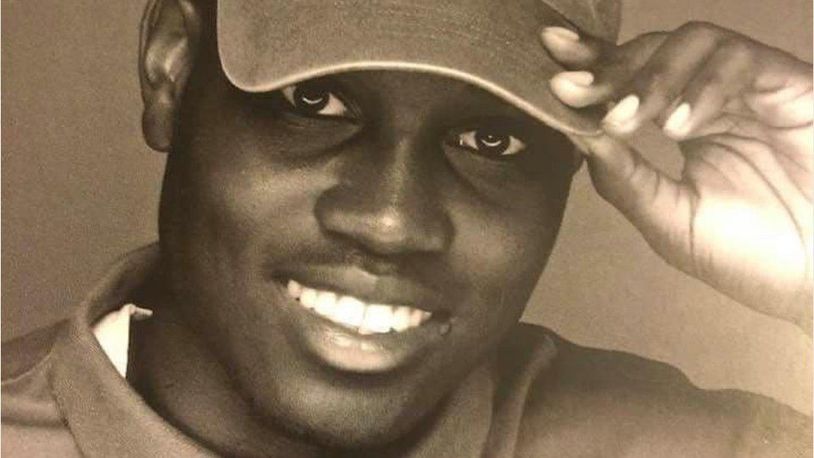

One example is the extrajudicial killing of Ahmaud Arbery in Brunswick, Ga. There is a video of his death, from the gunshot to his final breath. I’ve seen segments of it, but gone out of my way to not watch its entirety. In fact, after I witnessed Eric Garner’s video in 2014, I knew I could never again bear watching another one of my people die from gratuitous white violence.

The way Arbery’s body crumples to the ground in his last moments is absolutely worthy of representation. His fall epitomizes the wrath of white supremacy that still runs deep, especially in the American South. Yet, watching such videos exacerbates the experience of “black witnessing,” a term Alissa V. Richardson, assistant professor of journalism at USC, coined to describe the unique way in which Black people consume videos or spectacles of violence against other Black people.

Once, during my junior year of high school, I was in a class where we discussed current events and debated controversial topics. Two senior boys had tasked themselves with tormenting me any chance they got during that period: imitating me while I was speaking and mocking me for caring so deeply about social justice.

During that class, Terence Crutcher was killed by Betty Jo Shelby in Tulsa, Ok. We watched CNN’s live coverage of the event. I stared at the footage of a helicopter circling a car and dissociated. Then I heard one of my tormentors say: “it says right here that he had PCP in his car.” I was torn out of what I didn’t yet know was my own Black Witnessing experience, only to meet my classmates finding excuses justifying officer Shelby’s actions.

Black witnessing involves a bearing of victimhood, of “you see(ing) yourself (or) your family in the video” Richardson said in an interview with Vox. Black witnessing has also always been prohibited: she said in “the slave narrative (there are) all kinds of accounts of people who dare to look up while another slave was getting beaten, and then they received the beating, too.”

Videos of people like George Floyd, Eric Garner and even Sandra Bland (whose death wasn’t caught on tape) establish the undeniable fact that the black experience is inevitably intertwined with brutal racism. The video of Arbery shows the last few moments of his life, an unfortunate testament to his humanity that is worth celebrating and memorializing.

However, as I sit in my room with my phone in hand, Twitter at my fingertips, I cannot bring myself to watch that video. I imagine my father, a black man, in Arbery’s place. I imagine my brother careening to the ground after white supremacists hunted him down in their pickup truck. These images, though imagined, haunt me enough to know that it is against my morals to consume such content, and the American public should do some of the same moral consideration.